100 years after the death of Michael Collins I recall how his arch-enemy, Eamon de Valera, once personally admitted to me that “Michael Collins was a good man”.

My childhood encounter with Eamon de Valera occurred long before I formed views that are significantly inconsistent with those of the ‘Long Fella’, especially his thinking around social and moral issues.

But there is no denying that he is one of our nation’s founding fathers.

Here’s my story anyway!

My grandfather – also called David Dwane – was a school pal of de Valera, and went on to write the first biography of the man more fondly known as Dev, published in 1922.

So, in 1966, when the country went into a large-scale celebration of the golden jubilee of the Easter Rising, I was captured by the fervour of the time and decided to write to Eamon de Valera and request a private meeting with him, citing my connection with David Dwane, the elder. A few months earlier he had led the nation’s 50th anniversary commemoration of the 1916 Rising and had just been re-elected President of Ireland in the weeks before I wrote to him.

There were other notable events in 1966 too:

- Sean Lemass stepped down after seven years as Taoiseach, to be replaced by Jack Lynch

- Nelson’s Pillar, in the centre of Dublin, was bombed by Irish republicans, in a sign of dreadful things to come

- the UVF was reformed in Northern Ireland

- A free secondary school education scheme was announced

- Allied Irish Banks was created

- Sean T. O’Kelly, who was the second President of Ireland, died

Curiously, that same year, de Valera was honoured for his support for Irish Jews, and had a forest dedicated to him just outside Nazareth, with the approval of the Israeli government.

Ireland’s social and moral norms continued to change too. In February 1966 The Late Late Show famously earned a scolding from a the Roman Catholic church following some banter between its presenter, Gay Byrne, and a woman in the audience who claimed she did not wear a nightie on her wedding night! That controversy further polarised a growing liberal voice against the conservative society of 1960s Ireland, where Church and State enjoyed a special union!

My grandfather and Eamon de Valera were in the same class at national school in Bruree, Co. Limerick. In fact, they were born within a few weeks of each other, albeit in different countries – Dwane in Limerick and de Valera in New York. There was even talk in our family about a distant blood relationship between the Dwanes and de Valeras, through the Colls of Bruree, something that I have yet to research conclusively.

My grandfather, who wrote under the name of David T. Dwane, was a friend of Dev’s, and may have named my own father, Eamon Dwane, after ‘the Long Fella’.

David T. Dwane’s ‘Early Life of Eamonn de Valera’ was published against the backdrop of the War of Independence, and was meant to be an account of Dev’s life from boyhood to Easter Week 1916.

My grandfather, who worked in Kilmallock Post Office and also did some farming, was a staunch republican. In the book’s preface he writes of the many great escapes his manuscript had before eventually being published by Talbot Press in Dublin.

He began writing the work at a time when the British Crown forces were very active in seeking out and destroying any documents that made reference to the Sinn Fein movement. de Valera was President of Sinn Fein at the time, before he went on to form Fianna Fail in 1926.

He writes that his manuscript almost had as many escapes as de Valera himself. My grandfather’s home in Kilmallock was searched, but the document, hidden in a secret drawer of a writing desk, was not found. Other hiding places included a garden and a neighbour’s house. The British military later raided mailbags destined for Dublin that should have contained the manuscript but, due to an oversight, the text was still in the registered letter safe at the Post Office.

The many delays in getting the book to the printers meant that my grandfather was now able to include the period up to the Treaty in his biography. His book includes a full record of the names of those who voted for and against the Treaty in the ‘Second Dail’, constituency by constituency, including in the constituencies then called Mayo South and Roscommon South, Mayo North and West, and Sligo and Mayo East.

I was caught up in the intensity of the 50th anniversary celebrations of the 1916 Rising (the 2016 commemorations were a much more subdued affair). Just 10 years of age, I was very much aware of the significant contribution that the rebels of the Easter Rising had made to Irish freedom.

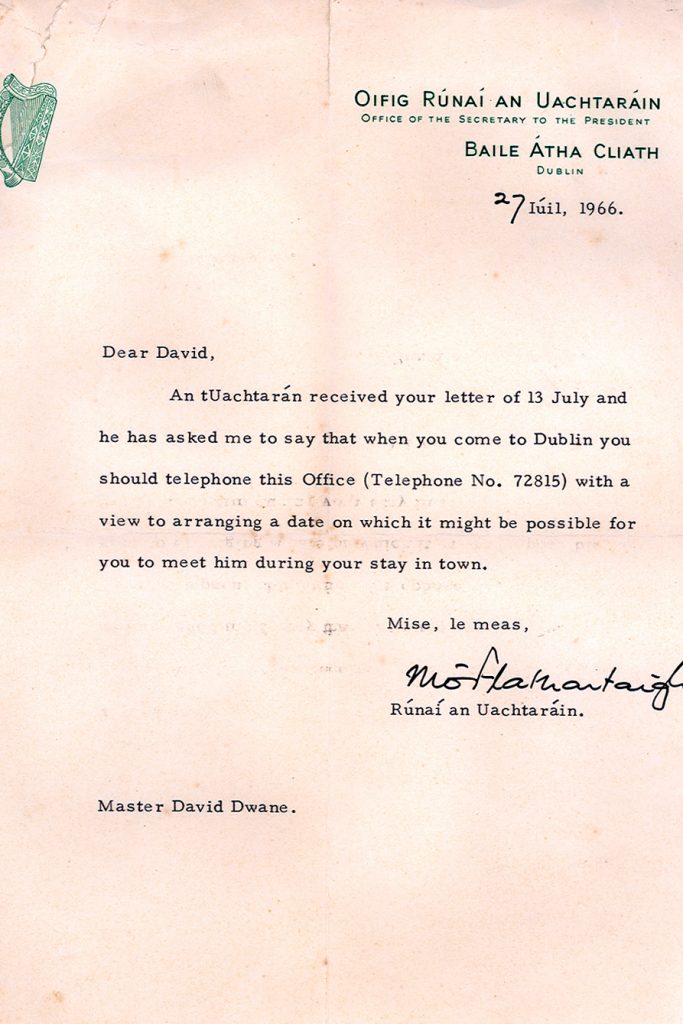

I wrote to Eamon de Valera in 1966, as I was finishing fourth class in Ballyhaunis National School, and received a letter back inviting me to contact Áras an Uachtaráin when I was next in Dublin, with a view to arranging a private audience with the President.

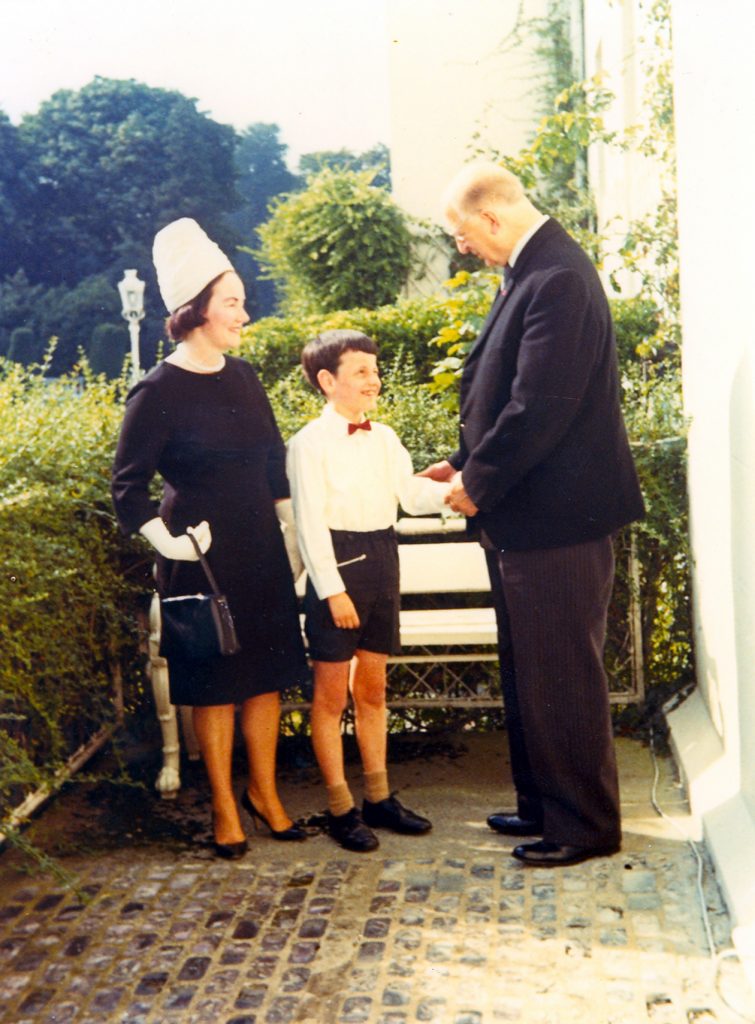

Thus, on a warm summer’s day in August 1966, I headed to the Áras with my mother, Rosaleen (nee Garvey, from Ballyhaunis).

A first, abiding memory I have of that visit is seeing a sentry outside the gates of the President’s residence bearing arms, the first time that I had seen a gun.

Once inside the splendid building we were shown to an elegant reception room. Mr. de Valera came in a few minutes later, a kindly, old man who smiled a lot. We chatted and had tea.

He was 83 at that time, and his eyesight was poor. But his mind was very sharp and his general health was good. I got the impression that he was really delighted to meet a descendant of his then-deceased good friend and school pal, especially a namesake.

I remember him being very interested to learn that my father Eamon Dwane had played hurling at county level and had won many provincial and national lawn tennis titles. de Valera himself had been an enthusiastic rugby player in his youth.

One question that popped into my head that afternoon, and oblivious to the delicacy of my query, was to ask Dev what he thought of Michael Collins. Possibly in deference to my young age, he replied to me that ‘He was a good man’.

Another recollection I have of our half hour meeting is that he posed a mathematical question to me, algebra, I think, offering me a ten shilling note if I got it correct. de Valera was a former maths teachers, but I was pretty hopeless at the subject, and failed the challenge. But I do remember being very disappointed that he didn’t give me the ten shilling note anyway!

Dev also spoke some Irish to us, some of which I did manage to grasp!

We had forgotten to bring a camera to record the occasion so Dev’s private secretary, Máire Ní Cheallaigh, kindly offered to take some photos on the impressive patio of the Presidential residence, and subsequently posted the colour prints to our home in Ballyhaunis.

Dev saw out his second seven-year term in the Áras and was the oldest Head of State in the world when he left office in 1973.

By that time I had started to form my own opinions around social and moral matters, and it transpired that the rightist policies of de Valera were quite inconsistent with my own views.

But history cannot be changed and I still treasure the opportunity that I had to meet a key figure in the birth of our nation.